Language and the Brain

The Language Problem

So, here I am again, after two years, wrestling with the language problem. The last time was when I was preparing a talk for a Bahá’í Conference on the etiquette of expression.

Then, as now, the words of Robert Graves came to mind. For a poet he was surprisingly suspicious of language:

There’s a cool web of language winds us in,

Retreat from too much joy or too much fear:

We grow sea green at last and coldly die

In brininess and volubility.

But concluded that we couldn’t stay sane without it:

But if we let our tongues lose self-possession,

Throwing off language and its watery clasp

. . . . .

We shall go mad no doubt and die that way.

I looked at a system of psychotherapy (Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: ACT), which draws on many traditions of psychology philosophy and spirituality, shares this same suspicion about language and seeks to undermine our simple confidence in it in various ways. For instance they point out that it can lead to such circular and irresolvable torments as:

This statement is false.

You have only to ponder that for a few seconds to realise there is no way out!

I found similar reservations in the Bahá’í Writings.

People for the most part delight in superstitions. They regard a single drop of the sea of delusion as preferable to an ocean of certitude. By holding fast unto names they deprive themselves of the inner reality and by clinging to vain imaginings they are kept back from the Dayspring of heavenly signs.

(Tablets of Bahá’u’lláh Haifa 1978: page 58)

Language is cast here in terms that summon up the idea of ‘veils’ as used in the sense of things that come between us and the truth.

Let not names shut you out as by a veil from Him Who is their Lord, even the name of Prophet, for such a name is but a creation of His utterance.

(Epistle to the Son of the Wolf: page 176)

Obviously names are not all there is to language. ACT uses language to cover all symbolic activity. They feel we are all too prone to mistake a metaphor, which is only a map after all, for the territory itself.

The way we get seduced by the deceptive certainty of our maps is an aspect of those problems in the political arena that I looked at in previous posts (one on party politics and the other on complexity and climate change). I hadn’t realised how deep the problem lies until a week ago when I began to read a certain book.

Its Roots in the Brain

The book was published late last year. It looks at this problem from another angle again and makes an impressive contribution to the debate. It is The Master and his Emissary by Ian McGilchrist. I am only just about a quarter of the way through but am already mightily impressed.

The book was published late last year. It looks at this problem from another angle again and makes an impressive contribution to the debate. It is The Master and his Emissary by Ian McGilchrist. I am only just about a quarter of the way through but am already mightily impressed.

At this point I’ll give only a couple of examples to illustrate why. I’m sure I won’t be able to resist revisiting this book in later posts rather in the same way as I kept going back to The Evolution of God of Is God a Delusion?

In the second chapter of McGilchrist’s book there is a section on Certainty.

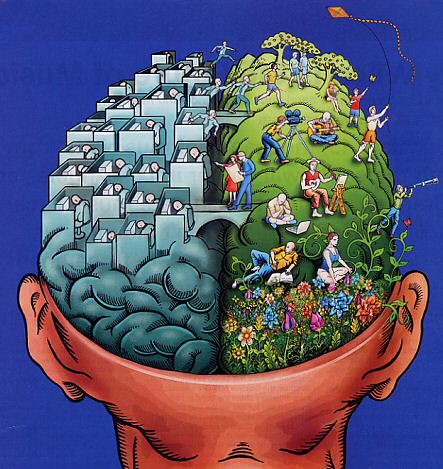

Before plunging in to the specifics here perhaps I need to explain that his book is about the way that the two hemispheres of the brain operate. His thesis is not the simplistic left-brain equals language and sequential processes and is the foundation of all our achievements in science while the right-brain deals with holistic arty stuff of little real value. He is not happy with the way our science-based civilisation deifies the left-brain mode but neither is he going to sign up to the opposite camp that wants to glorifies the stereotype of the right hemisphere as the intuitive and organic guru, the one to follow. He is keen not to quarantine the left-hemisphere in the Hades occupied by tyrants when they’re overthrown.

He digs much deeper. He accepts that there is something contradictory about the way the two hemispheres of the brain work. He argues that the price of the relative suppression of the right in favour of the left has not been properly understood because we have disparaged the necessary and considerable abilities of the right hemisphere. However, we should be seeking to re-establish the right balance between them not reinforcing some kind of competition. If either hemisphere wins the race outright it will be no better than if we hopped around for the rest of our lives using only one leg.

So, back to his thought about certainty.

The left hemisphere likes things that are man-made. Things we make are also more certain . . . . They are not, like living things, constantly changing and moving, beyond our grasp.

(page 79)

Language, he argues, is a tool of the left-hemisphere in its battle to control and manipulate reality. It tends to relate to the world of the living as though it was all a machine of some kind that can be captured by analysis. Language provides its main map of reality, a representation, which the left-hemisphere in its hubris insists is all there is to know.

The Hemispheres

Because the right hemisphere sees things as they are . . . . it cannot have the certainty of knowledge that comes from being able to fix things and isolate them. In order to remain true to what is, it does not form abstractions, and categories that are based on abstraction, which are the strengths of denotative language. By contrast, the right hemisphere’s interest in language lies in all the things that help to take it beyond the limiting effects of denotation to connotation: it acknowledges the importance of ambiguity. It therefore is virtually silent, relatively shifting and uncertain, where the left hemisphere, by contrast, may be unreasonably, even stubbornly, convinced of its own correctness. As John Cutting puts it, despite ‘an astonishing degree of ignorance on the part of the left (supposed major) hemisphere about what its partner, the right (supposed minor) hemisphere, [is] up to, [it] abrogates decision-making to itself in the absence of any rational evidence as to what is going on.’

(page 80)

He goes onto summarise this:

So the left hemisphere needs certainty and needs to be right. The right hemisphere makes it possible to hold several ambiguous possibilities in suspension together without premature closure on the outcome. . . .The right hemisphere is able to maintain ambiguous mental representations in the face of the tendency to premature over-interpretation by the left hemisphere. The right hemisphere’s tolerance of uncertainty is implied everywhere in its subtle ability to use metaphor, irony, humour, all of which depend upon not prematurely resolving ambiguities.

(page 82)

All of this is grounded in a mass of evidence that there is not the space to include here.

He then moves onto an equally fascinating topic: morality.

He sees the left hemisphere as fixated on utility. If something isn’t useful in some obvious practical sense it’s a waste of time.

Moral values are not something that we work out rationally on the principle of utility, or any other principle for that matter, but are irreducible aspects of the phenomenal world, like colour. . . . . [M]oral value is a form of experience irreducible to any other kind, or accountable for on any other terms; and I believe this perception underlies Kant’s derivation of God from the existence of moral values, rather than moral values from the existence of God. Such values are linked to the capacity for empathy, not reasoning; and moral judgements are not deliberative but unconscious and intuitive, deeply bound up with out emotional sensitivity to others.

(page 86)

He points out the organic basis for this and I feel I need to quote it this time:

The Brain

Moral judgement involves a complex right-hemisphere network, particularly the right ventromedial and orbitofrontal cortex, as well as the amygdala in both hemispheres. Damage to the right prefrontal cortex may lead to frank psychopathic behaviour.

(Ibid)

The amygdala can perhaps be called the emotional centre of the brain and is relatively old in evolutionary terms. The others are all part of the higher brain centres in the right hemisphere which came along later.

Given how central the idea of justice is in Bahá’í thinking, it is also intriguing to find it has has its own seat in the brain:

Our sense of justice is underwritten by the right hemisphere, particularly by the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. . . . . The right frontal lobe’s capacity to inhibit our natural impulse to selfishness means that it is also the area on which we most rely for self-control and the power to resist temptation.

(page 86)

There is also (page 92) apparently ‘a slow accumulation of evidence in favour of religious experience being more closely linked with the “non-dominant” hemisphere.’

Conclusion So Far

I am now poised at the beginning of my exploration of his unpacking further implications of all this. I have just got past the bit that says:

I believe the essential difference between the right hemisphere and the left hemisphere is that the right hemisphere pays attention to the Other, whatever it is that exists apart from ourselves, with which it sees itself as in profound relation. . . . By contrast, the left hemisphere pays attention to the virtual world that it has created, which is self-consistent, but self-contained, ultimately disconnected from the Other, making it powerful, but ultimately only able to operate on, and to know, itself.

(page 93)

If these ideas have grabbed your imagination as much as they have grabbed mine, may be you won’t be able to wait for the drip-feed of bits and pieces that will come via this blog over the next few weeks. Perhaps you will prefer to go out and buy the book for yourself. I think it would be well-worth it.

No comments:

Post a Comment